Does Your Pet Like One Person in Your Relationship More?

Pet jealousy can become a thing if one partner feels like the cat or dog is just not that into them.

Heavy Pettingopens in new tab is a weekly column full of relationship advice for pet parents — so you and your boo don’t end up fighting like cats and dogs over the cat and dog.

“You treat the dogs better than you treat me,” my friend Dave says to his wife, Alice, while the three of us are having dinner. Alice laughed. Dave laughs, too — but not as much.

Later, when Dave and I are alone, I ask him if he meant what he said.

“No,” he says. “I was just joking.”

How much do you spend on your pet per year?

But it didn’t feel like a joke. It felt like one of those things you joke about, because you’re too scared to talk about it seriously. Because what does it say about you that you might be jealous of your own pet? What does it say about your relationship?

If this was the only time I heard Dave talk like this, I might not think much of it. But this was coming at the end of a long weekend together, when I had already taken note of what struck me as Dave’s jealousy toward the dogs and their relationship with Alice. Once, he tried to get the dogs’ attention, but they just stood by the door, waiting for her to return from the car: “Well, I guess I’m just a piece of shit, then,” he said with a laugh.

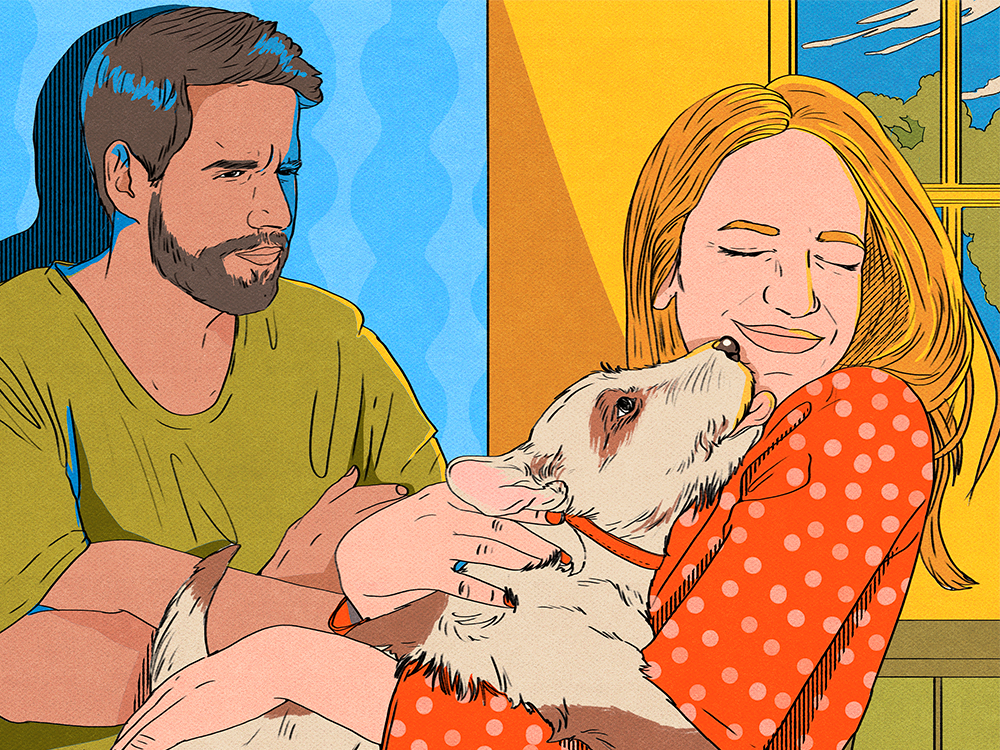

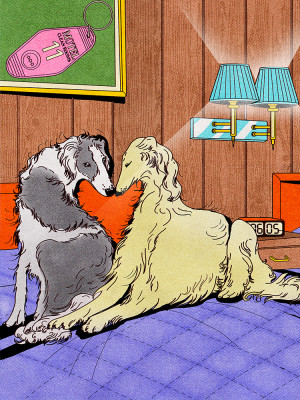

Although, again, it didn’t feel that funny. Or when we were all hanging out in the living room, and I watched him watching her — his face wan — as she sat stroking the dogs crowded in on either side of her, and I wondered: “What would happen if Dave tried to snuggle in right now? Would they let him? Would she?”

Apparently, pet jealousy is a common relationship problem.

Licensed mental health counselor Kelly Scott, of Tribeca Therapyopens in new tab in New York City, has experience with pet-directed jealousy. Couples don’t come into her office planning to talk about it, but it does sometimes come up over the course of treatment. And when it does, it is always symptomatic of deeper issues within the relationship. “It’s never actually about the pet,” she says. “When we talk about jealousy, what we’re really talking about is scarcity — the idea that there is only so much care and affection to go around.”

Of course, the amount of love someone has to give is not finite. The energy we have to provide care to others might be limited, but our capacity for love is not. And yet, if a person in a relationship feels like they are not getting enough love from their partner, they might start to view that love as a limited resource — even if subconsciously — and resent the dog or cat who is the recipient of that love. It’s not the pet’s fault, of course, but it is easier and safer to blame a pet than it is to hold yourself and your partner accountable for the issues in your relationship.

Pets are a good scapegoat because they don’t have agency in the same way humans do. They can’t speak up for themselves and are dependent on us in many ways. Indeed, much of what we think of as their “personalities” is often just a projection of our own wants and needs, and the narratives we concoct to make sense of their behavior. In reality, our pets are who and what we say they are. A human partner can and will challenge our perceptions of them, but a pet never will and never can. That’s what makes them so easy to love. And easier to blame.

And it’s important to address the real causes of the problem.

Justified or not, once resentment takes hold, it must be addressed. “Resentment without intervention, discussion, exploration, and engagement will only amplify,” Scott says. “I find it incredibly rare that people who feel resentment ever just ‘get over it.’ It’s what I call a ‘sticky feeling.’ It is incredibly toxic in relationships and needs attention.”

But before you can get help with an issue, you first have to admit it exists. Many of the friends I spoke to for this article, seemed to feel like the idea of pet-directed jealousy was silly. Certainly not something worthy of serious discussion.

“That is so stupid,” my friend Jamie says when I ask if she thought her husband, Greg, had ever been jealous of her cat, Maxine. “Who would be jealous of a cat?”

“People feel how they feel,” I say.

“Yeah, but I don’t think Greg ever felt jealous of her. He didn’t even like her.”

Immediately, I think, But don’t dislike and jealousy often go hand in hand?

“I was never jealous of that cat,” Greg responds.

Fair enough. Greg was never really a cat person anyway. And he always seemed perfectly fine with the fact that Maxine wanted absolutely nothing to do with him. She wanted nothing to do with anyone. Except Jamie, of course. Jamie could bury her face in Maxine’s belly and blow raspberries if she wanted to. Anyone else trying that would come back without a face.

But I could also imagine a world where Greg would be jealous. I could see a situation in which he felt resentful of the love his wife was giving to a creature who treated him with such disdain. I could see him as resentful of the mere existence of a loving relationship in his own home from which he was excluded.

“Seeing two creatures share a bond that you feel excluded from can be difficult,” Scott adds. “It can make you feel insecure and make you wonder what it is about you that they don’t like.”

Even if it’s not the mature thing to feel, jealousy and resentment happen.

When I was a kid, my mother had a cat, Sophie, who wanted nothing to do with me. She only liked my mom and would sit on her lap while she read and hang out with her while she cooked. I didn’t understand why Sophie didn’t like me and, looking back, I think I resented her for taking my mother’s attention away from me. Of course, I was just a little kid at the time. I like to think I wouldn’t be jealous and resentful of Sophie now. I like to think I’m more mature than that. But adults often do and think childish things. And just because a feeling is embarrassing or doesn’t align with the way we see ourselves, doesn’t mean it isn’t real.

My friend Leah, for example, often expresses feelings of jealousy about the relationship between her boyfriend, Michael, and their cat, Boots. Although she doesn’t like that word: jealousy.

“I’m not jealous,” she tells me.

“But I’ve seen you pouting when Boots chooses to sit on Michael’s lap instead of yours.”

“I’m not jealous, though,” she says. “I just want him to c uddle with me, and he only ever cuddles with Michael.”

I have seen Boots cuddle with Leah, though. She’s even sent me photos of Boots sleeping on her lap. But that usually only happens when Michael isn’t home. When he’s around, Boots’s preference is clear. And the way Leah expresses her feelings about that preference: begging Boots to come sit with her instead of Michael and acting upset (even if only briefly) when he doesn’t, looks like jealousy to me.

Call your feelings what they are, and don’t be embarrassed by them.

Of course, it’s possible I’m misreading the situation entirely. Maybe this is just a performance. A game. Then again, maybe Leah is just unwilling to admit the truth about her feelings, because, like my other friends, the idea of being jealous of a cat seems so ridiculous to her.

“It is essential that you acknowledge how you feel,” Scott says. “Don’t judge yourself, like, ‘Oh, that’s stupid. I can’t be jealous of a cat or a dog.’ Judging yourself like that prevents you from exploring and understanding your feelings. And without that understanding, you can’t begin the work of figuring out how to address them.”

Once you admit the feelings exist, Scott recommends starting a conversation with your partner to address them. “Issues like this are often the result of misunderstandings and assumptions on both sides,” Scott says. “And sometimes, all it takes to resolve them is one conversation. And if it’s too hard to talk about alone, then you need to get help. Ultimately, though, if you want it to get better, you have to talk about it.”