5 Science-Backed Ways to De-Stress Outdoors (Your Pet Is Invited)

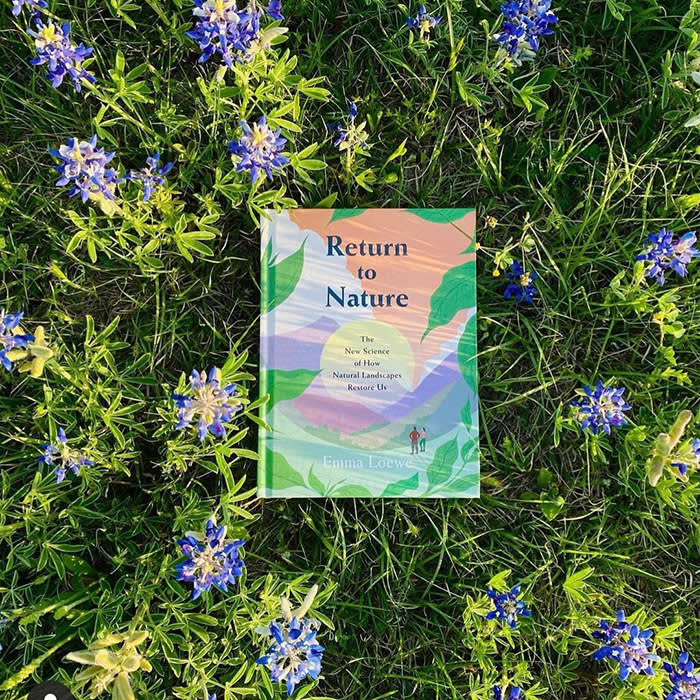

The author of Return to Nature on the mental health benefits of getting out into various natural landscapes with your pup.

My book, Return To Natureopens in new tab, is all about the mental health benefits of getting out into various natural landscapes. It walks you through how to make every visit to the beach, the river, or just the trees near your home even more restorative. In this excerpt, I share science-backed ways to make the most of your time on mountains and trails this spring — and you can totally bring your pet along for the journey.

Whether you’re heading out on a backpacking trip, going on a day hike, or taking in a mountain view from ground level, here are some ideas for enhancing the journey.

Walk up a trail slowly, without a destination in mind.

Even if you don’t have time to gain much elevation, you can still have a memorable experience on a mountain trail. Denise Mitten, sustainability and adventure education professor and nature health researcher at Prescott College, tells me that even mundane moments can be transformative so long as we approach them with an open mind. “It seems like people in general have transformative experiences when they’re open to what’s going on, when they don’t have an agenda of how they think things should be,” Mitten says. This happens when we see the land around us as a space to leisurely traverse rather than quickly get through.

“Pace makes a huge difference,” she adds. “So stop and smell the roses — seriously.” In this more meandering state, you might find yourself noticing more of what landscape has to offer.

How much do you spend on your pet per year?

Expand the breath to eleven counts in the presence of mountains.

Awe researcher Melanie Rudd has found that slow and controlled breathing can ground us in the present moment and subsequently expand our sense of timeopens in new tab.

Apply this research by following a slow, mindful breath pattern of a five-second inhale and six-second exhale as you gaze at a mountain view in order to open yourself up to, as Rudd puts it, be awed by something you might not have noticed or fully appreciated otherwise.

Consider a problem at the start of your hike, and write about it at the end.

Before you start your climb, consider one problem you’re facing or one area of your life where you could use some clarity. At the end of the hike, free-write on it and see if you’ve stumbled across any new insights during the journey.

This ritual is inspired by Bonnie Smith Whitehouse, an English professor at Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee, who lectures on the creative inspiration that lies in nature using some unique methods: when I interviewed Whitehouse for an article in 2019opens in new tab, she told me how one class a semester, she’ll have her students journal on a question before starting a hard hike and then come back to it every time they needed to take a break on the way to a summit.

She encourages them to “focus on your footsteps and your breathing” along the way, and then use their journals to extract any insights that came up during the experience. “When you combine walking and journaling,” she said, “it can really pack a punch for your well-being.”

Revisit the same route season after season.

In most parts of the world, a trail will look different in winter than in summer. The seasonal shift is a reminder that time changes everything, and it’s why the Good Grief walking program in Calgary brings participants who are mourning the loss of a loved one on the same walk on the same trail multiple times throughout the year.

Sonya Jakubec, a mental health nurse and associate professor at Mount Royal University who works with the program, tells me this revisiting can cause people to consider how their inner landscapes have gone through a transformation since the last time they walked through that area: how their grief and loss looks different in the new surroundings. Whether you’re grieving or not, going on a hike with the intention of using nature’s cycles as a cue to tune in to your own cycle is always valuable practice.

Wander somewhere that feels untouched by humans.

During his career as a superintendent with the National Park Service, Dan Wenk watched as most visitors hurriedly drove Yellowstone’s main roads, stopping at attraction after attraction to tick boxes off a bucket list, without indulging in the over one thousand miles of backcountry trail the park had to offer.

Keenan Adams, a federal public land manager based in Puerto Rico, has noticed something similar in his neck of the woods: “People experience a fraction of public land because they stay on the beaten path. To get a different public land experience, you need to get off the beaten path,” he tells me.

Many of the gifts of the mountains reveal themselves slowly: settling in a species-rich area, stumbling on an awe-inspiring view, and walking until ruminative loops are broken all take time. Only when we loosen our grip on our schedules and let the landscape take us where it will do we open ourselves up to the “emotional renewal,” as Wenk describes it to me, that comes when we are totally alone with nature, our thoughts, and our experience.

Excerpted from Return to Nature by Emma Loewe and reprinted with permission from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright 2022.