The Bewitching History of Black Cats and Halloween

How witches, the original cat ladies, and their feline familiars became culturally bound to All Hallows’ Eve.

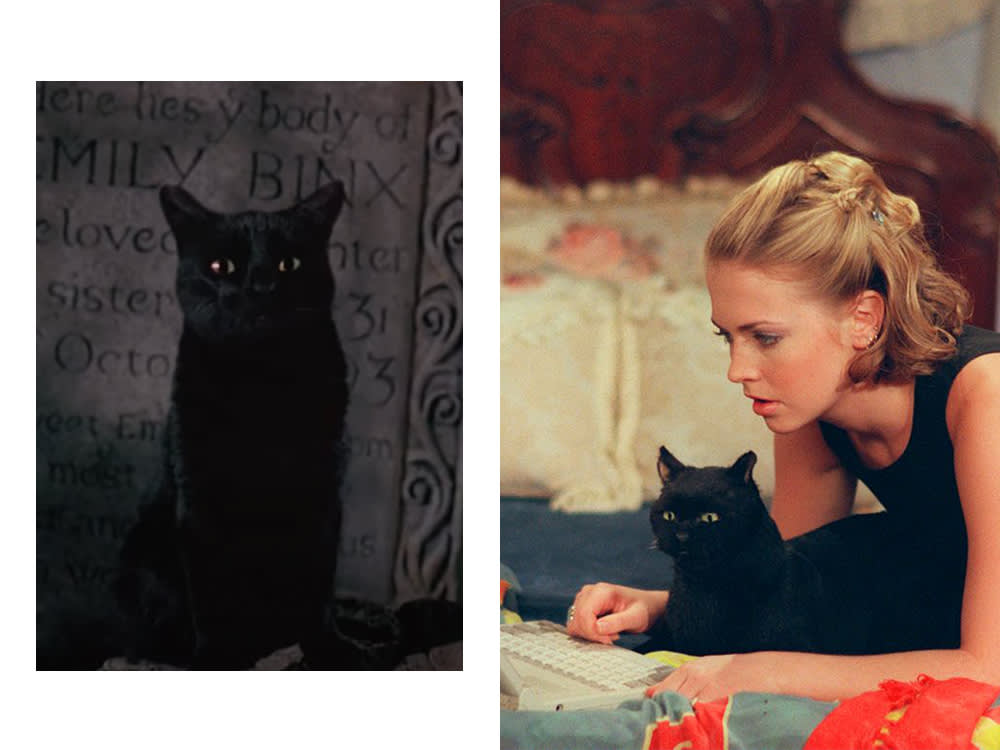

“Thackery Binx, thou mangy feline!” Give the cat a break. By the time Bette Midler hexed a human boy to live forever as a black cat in Hocus Pocus, the breed had already survived its heap of curses. Inheriting a history of superstition and abjection leading back to history’s first cat ladies, it’s no wonder that Binx, like his other pop-culture black cat contemporaries, met life with a smarmy disdain. Whether they’re dueling to the death as in Hocus Pocus, or bound at each other’s side, like Sabrina and her familiar, Salem, what makes black cats and witches so intimately connected — and mutually scorned? And how did the two become so intrinsic to the tradition of Halloween?

Witches and cats in the shadows

Although black cats were worshipped in Ancient Egypt, with mythological footholds all over the world, their direct connection to Halloween began around 2,000 years ago, among the Celtic tribes based around Ireland. Druidic culture was pagan and often matrilineal, involving a pantheon of gods and animalistic spirits, witches, or “wise ones,” who acted as healers, tribal leaders, and sages. Many festivals and ceremonies took place at night, giving a certain allure to those nocturnal animals who thrived in the dark, especially the black cat, ever elusive in the shadows.

Save on the litter with color-changing tech that helps you better care for your cat.

Some Celtic traditions believed that those who played with dark magic would be turned into cats, pitting cats and witches on two sides of a moral divide. On Samhain, the autumnal celebration in which the veils between this realm and the next are opened, revelers would wear costumes made of animal skins and heads, invoking their gods and banishing away dark forces. This tradition would continue into contemporary usage. But soon women would be considered as dangerous as the feline shadow totems, and both would be lumped into the same pyre of superstition.

The all-new, all-male Holy Trinity didn’t have space for a woman, let alone a powerful, capable, and, incidentally, often single tribal leader. The Church easily made medicine women into hags and harpies, and linked any traditions outside of papal canon to devil worship. The witches found themselves inheriting black cats; now it was believed that the witches could shift into feline form, or that the cats were their familiars — demon guides given to them by the devil.

How much do you spend on your pet per year?

By the Middle Ages, the church had assimilated Samhain, transferring its key practices to All Saints’ Day on November 1. As the bubonic plague ravaged Europe, spread by infected rats, those women who were once revered as healers, and the cats who hunted such vermin, were castigated as the cause.opens in new tab Such devastating death could only be traced to the devil, his harlot priestesses, and their pitch-black, shadowy feline companions. Even with Samhain cut out officially, its practices never died, and the night before All Saints’ Day, with all its enduring bonfires, costumes, and parties, became All Hallow’s Eve — Halloween.

The New World and spooky season

The drip-drip Puritans didn’t believe in saints, so All Saints Day stayed in the old country when they arrived in the New World. And so the tradition continued: Who better to blame for a poor harvest or bad luck in the colonies than a certain kind of woman? Witches were easy targets: women had no legal rights and couldn’t own property, putting those without a husband or father to “claim” them at the top of the heap. The stigma extended now to black women, thought to practice an exotic form of fortune-telling. As ever, the vexing, intractable, unknowable black cat symbolized all that could not be controlled or contained in these noncompliant women.

Black cats would hold their dark majesty in folktales and spooky stories often shared at autumn festivals. Ghost stories and “play parties” abound during these colonial harvest festivals. But the arrival of Irish immigrants in the 19th century brought a resurgence of All Saints’ traditions, including “souling” — in which poor townspeopleopens in new tab would knock on the doors of the wealthy and take money to pray for their beloved dead — which would later feed into the trick-or-treat tradition. Unbound from puritanical constriction, more post-pagan traditions could abound, and by the turn of the century, Halloween had been secularized into a community-oriented celebration. By the ’60s, the old traditions had to become kitsch, camp, and publicly accessible, so the revenant spirits, scary witches, and devil-delivered black cats were renewed and repopularized.

Black cats in culture

Beyond the Halloween industrial complex, blacks cats have made it into union halls and even spacecraft. At the turn of the 20th century, labor organizers used the image of a screeching black cat, known as “sabo-tabby,”opens in new tab as a symbol for strikes and sabotage. Black has long been associated with anarchy, and the vigilant cat perfectly symbolized the outsider ideals of many revolutionary laborers. In the ’80s, NASA’s 11th space shuttle mission was to be titled STS-13. Fearing the number’s bad luck, especially after the difficulties faced by the Apollo 13 in the ’70s, NASA changed the mission’s sequence number, but the crew, daring superstition, made patchesopens in new tab, featuring a black cat and the number 13, and eventually brought the craft to successful landing on Friday the 13th.

In terms of popular lore, folktales involving black cats crept up from the American South from the 19th century on, including the popular Wait Until Emmett Comes.opens in new tab But the course of black cat cultural awareness was changed forever in 1843, with the publication of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Black Cat. Although Poe was particularly fond of cats, like his beloved companion Catterina, he centered Pluto, the protagonist of this grisly short story, as a figure of menace. The madman at the heart of The Black Cat takes a love for animals to violent levels of sadism. While Poe employed the figure of a black cat to symbolize issues of guilt, isolation, insanity, and alcoholism, the horrific visuals did the trick, sealing the breed’s place in the shadows for over a century to come.

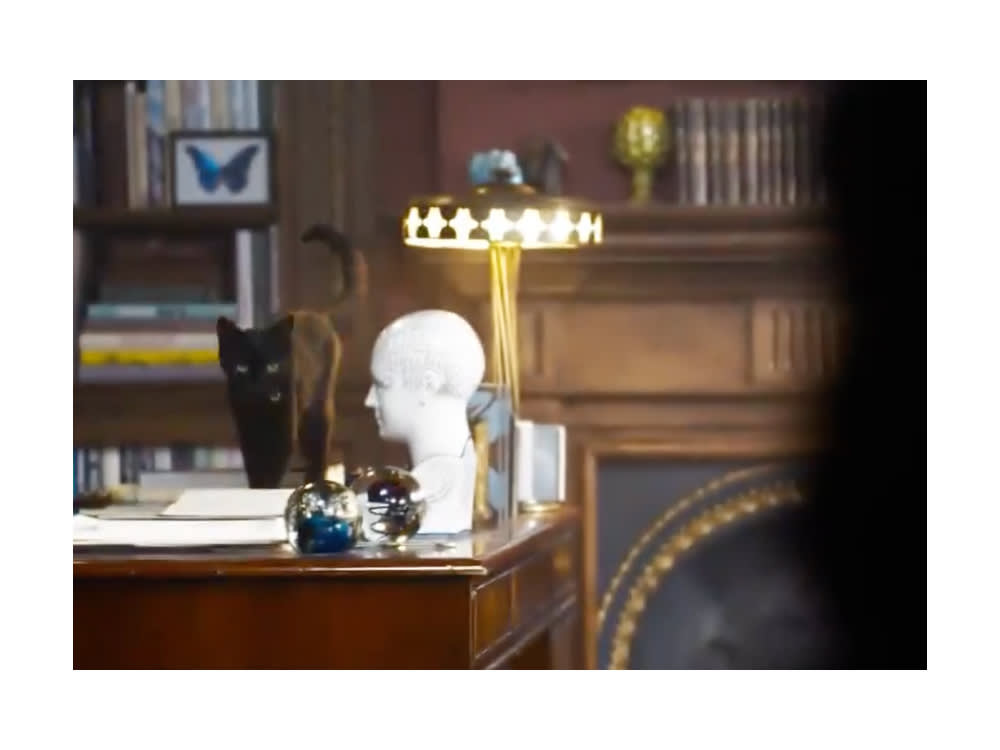

Poe’s story would spawn dozens of screen adaptations, including a 1962 edition of Tales of Terror, 1965’s The Tomb of Ligeia and a very loose 1981 film adaptation involving a professor with psychic powers. But beyond Poe, the black cat’s genre popularity was unstoppable, with 1934’s hit The Black Cat — no relation to Poe — which involves Béla Lugosi, Boris Karloff, and satanic cults. Perhaps the contrast of black-and-white film served the cat’s dark mystique best of all. The breed would generally serve as an omen of bad tidings for the better part of the 20th century, like in 1973’s The Legend of Hell House.

But leave it to Hayao Miyazaki to change the game, with 1989’s Kiki’s Delivery Service. This time, the witch, Kiki, was a charming 13-year-old, and her cat, Jiji, couldn’t scare a fly. Voiced by the comedian Phil Hartman in the American adaptation, Jiji spoke with a bitter, know-it-all attitude that would serve his future animated compatriots. With the VHS boom of the ’90s, in which stars like the Olsen twins could make Halloween content for kids, the black cat found new life.

They returned to their role as guides, bringing their history of rough life experiences to aid otherwise naive protagonists. Why be typecast as a portent of doom when you can claim the role of salty sidekick? Suddenly, they were everywhere: Melissa Joan Hart bandied with Salem (Nicholas Bakay) on Sabrina the Teenage Witch; Coraline received reluctant aid from the can’t-be-bothered Cat, voiced by Keith David in the 2009 film adaptation; and Thackery Binx would come to love Thora Birch in Hocus Pocus.

With parallel resurgences in witch and cat lady cultures in the ’90s and 2010s, powerful, single witch women would count on their black cats for companionship and protection, rather than dry asides: the libertidinous Gillian (Nicole Kidman) clings to her companion, who correctly hisses at her undead ex, in Practical Magic; Sabrina’s Salem would be reenvisioned as a demonic powerhouse in 2018’s reboot Chilling Adventures of Sabrina; and the witch cop Rowan Black would stay close to her pet Hawthorne in the mature comic book series Black Magick.

Black cats switch from abject omens to truth-telling feminist avatars, depending on the dominating forces at work in popular storytelling. But perhaps the breed’s most complete depiction is in The Matrix, when one slinks just past Neo’s sight, indicating a déjà vu, a glitch in the false reality. Since the Druid rites, the black cat has symbolized the indelible, the unknown, the unconquerable. They’re a portal to a new reality, a silent crawl into the unknown night. Good luck trying to pin them down.