An Active Dog Is a Well-Behaved Dog

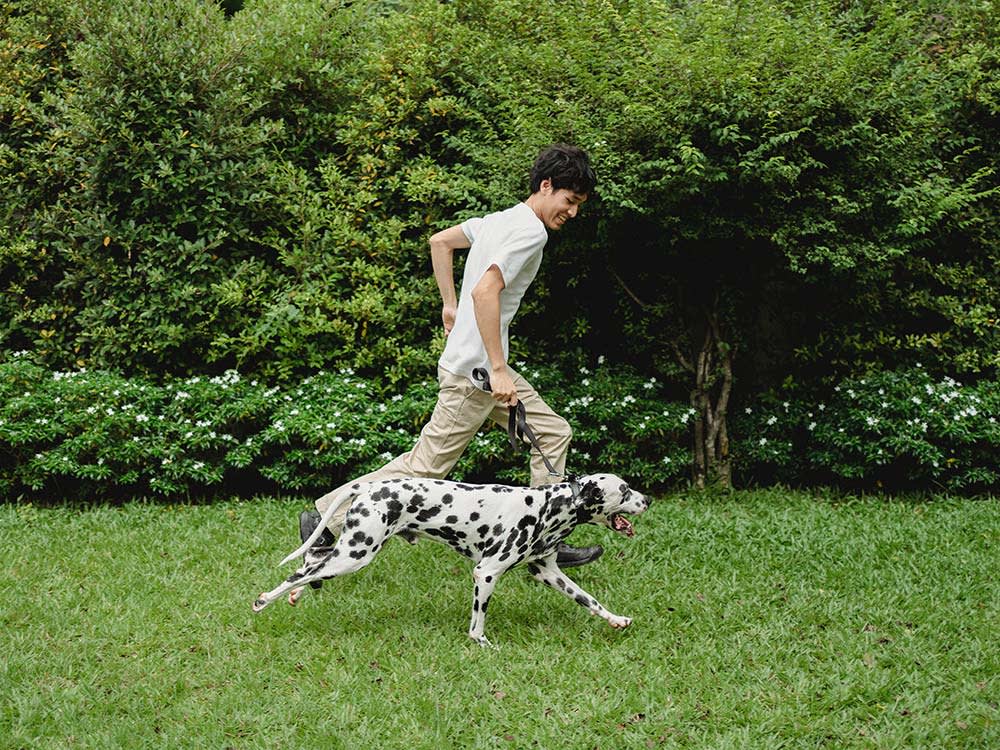

Why regular exercise can mean a less destructive dog and a happier you.

Changing any behavior takes time, patience, and dedication. When dogs are feeling mischievous, anxious, or stressed, they can cause a lot of damage — chewing shoes, counter surfing, scratching, barking — the list of undesirable behaviors goes on. Animal shelters are filled with pets abandoned because people don’t realize the time and dedication required to train good manners. While there is rarely a quick fix for anything, regular exercise can provide a huge benefit. Even with well-trained dogs, exercise matters if you want good behavior.

What should you do about destructive dog behaviors?

Training obviously helps with problem behaviors, but it’s not the only way to avoid trouble. Dog trainers have long valued the role of exercise in minimizing destructive dog behaviors such as barking, chewing, jumping around, being unable to settle down or sleep well, digging, whining, and relentless attention-seeking. Studiesopens in new tab show that more exercise was correlated with lower levels of fear, less aggression toward familiar dogs, and reduced excitability.

In one study, a group of dogs was divided in half; one half worked on formal training while the other half had their exercise increased to two 30-to-45-minute sessions a day. After six weeks, the dogs who had additional training showed improvements in both their responsiveness to cues and their problem behaviors. The dogs who had extra exercise also exhibited problem behaviors less frequently, although their responsiveness to cues had not improved. So, how does exercise affect behavior through physiological means?

How does exercise improve dog behaviors?

Like people, dogs can achieve an emotional state described as a “runner’s high,” which may be why your pup is so excited for the chance to go out on a run. It may also be why so many people believe the old saying, “A tired dog is a good dog.” But these well-behaved and well-exercised dogs may be more influenced by chemistry than by fatigue.

How much do you spend on your pet per year?

A runner’s high is caused by chemicals called endocannabinoids, which signal the reward centers of the brain. Endocannabinoids lessen both pain and anxiety as well as create feelings of well-being. Running triggers higher levels of these compounds, which is why running makes people (and dogs) feel good.

If you’re laughing at the thought and can’t imagine putting yourself through the misery of running on purpose, you aren’t alone. While most dogs are excited about running, humans, on the other hand — outside of a small percentage — aren’t interested. Still, the potential to activate the chemicals that cause a runner’s high exists within you — even if you aren’t dipping into it as frequently as your long-ago ancestors, for whom running long distances was part of daily life.

This pleasurable, rewarding quirk of chemistry is not universal among mammals. In a studyopens in new tab investigating the phenomenon of the “runner’s high,” researchers predicted that running would result in pleasurable chemical reactions in species with a history of endurance running. They studied three types of mammals — humans, dogs, and ferrets — and found that the two with distance running in their evolutionary pasts (humans and dogs) exhibited elevated levels of one particular endocannabinoid (anandamide) after running on a treadmill. Ferrets, non-cursorial animals, had no such chemical response and derived no pleasure from it. (Now you might be wondering if you’re part ferret.)

A happy dog is a good dog.

The behavioral benefits of running may be related more to contentment than fatigue. Perhaps, what we call “tired” is actually better described as “happy,” “relieved of anxiety and pain,” and “experiencing feelings of well-being.” If so, exercise may indirectly benefit dogs’ behavior because it elevates mood rather than simply makes them too worn out to misbehave. Since endocannabinoids lessen the anxiety that can be a source of problem behaviors, it’s easy to see how exercise could help.

Running is also associated with the production of other chemicals that reduce anxiety in mammalian brains. Researchers reportedopens in new tab that mice given the opportunity to run handled stress and anxiety better than sedentary mice. The study observed the brain activity in both groups of mice and found that runners had more excitable neurons in the ventral hippocampus — which plays a role in anxiety — than sedentary mice.

The active mice, however, also had more cells capable of producing the calming chemicals that inhibit activity in that area of the brain, which lessens anxiety. The study supports the idea that for mice, at least, running improves the regulation of anxiety through inhibitory activity in the brain. It is possible that the situation is similar in dogs, though without studying them specifically, we can’t know for sure.

What does this mean for your dog?

Of course, behavior and physiology, and the links between the two, are never completely straightforward. There is evidence that cannabinoids can cause hyperactivity at low doses, even though they have calming effects at higher doses.

Age, breed, and individual differences play a role in the amount of exercise required to keep your dog’s halo on straight and prevent them from sprouting little horns, behaviorally speaking. Some dogs thrive on small amounts of exercise. For others, the same amount of exercise — perhaps a leash walk at a leisurely pace — has the opposite effect. It invigorates them and may actually induce hyperactivity. For example, for a dog that typically runs 60 to 70 miles a week, switching to shorter exercise sessions for one week (say during a vacation) might actually just amp them up.

Your dog will also experience different effects from various amounts and types of exercise (running, hiking, swimming, playing tug, or fetch). When looking at ways to help reduce your dog’s destructive behaviors, you’ll need to find the right balance of training and exercise to help ensure that your pup is content.

Besides the well-known physical benefits of exercise, its psychological and behavioral benefits are profound. Stopping annoying behaviors and increasing good behaviors make the beautiful relationship between people and dogs that much better. What more could you want for your dog than the highest quality of life, minimal anxiety, the most elevated feelings of contentedness, and the best possible relationship with you?